Where Nature and Mystery Meet: Journey into the Heart of South Sudan

When the Map Fades, South Sudan Begins

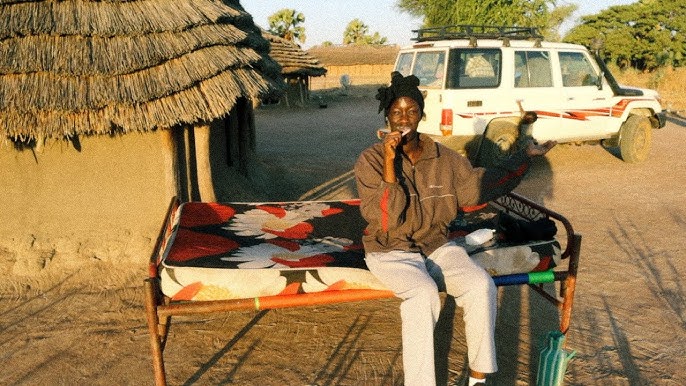

When most travelers think of Africa, images of safari jeeps in Kenya, the pyramids of Egypt, or Cape Town’s Table Mountain typically come to mind. Yet, nestled deep in East-Central Africa lies a land unlike any other: South Sudan — a place where the map of modern travel ends and a more primal, unfiltered world begins.

As the world’s youngest country, gaining independence in 2011, South Sudan is rarely found on bucket lists. But for the cultural explorer, the anthropologist at heart, or the traveler disillusioned with tourist traps, this is where Africa whispers its oldest stories.

This isn’t a blog about spa retreats or luxury safari tents. It’s about the elemental — bone, fire, ash, and blood. It’s about people who shape their bodies and beliefs through nature, hardship, and heritage. It’s about tribes who live in harmony with cattle, who paint their skin with ash, and whose towering frames make them giants — both literally and metaphorically.

The Dinka and Mundari: South Sudan’s Towering Guardians

Among the many ethnic groups in South Sudan, two stand out for their striking presence and deep traditions: the Dinka and the Mundari.

The Dinka are often regarded as the tallest ethnic group in the world. With average male heights around 6’2” — and many individuals nearing or exceeding 7 feet — they cut a formidable figure. Scientific studies point to a combination of genetics and a diet high in dairy and protein, fueled by their pastoralist way of life.

The Mundari, their neighbors and cultural cousins, may be smaller in population, but rival them in mystique. They are best known for their intimate relationship with cattle, elaborate hairstyles dyed with cow urine, ash-covered skin, and hauntingly beautiful rituals.

Both tribes offer a window into a lifestyle almost untouched by globalization — where identity is inseparable from land, livestock, and lineage.

More Than Livestock: Cattle as Soulmates

To understand these tribes, you must first understand the sacred cow.

For the Dinka and Mundari, cattle are not just animals. They are:

-

Currency — for dowries, disputes, and ceremonies.

-

Status symbols — the more cattle you own, the more powerful and respected you are.

-

Spiritual beings — often named, sung to, decorated, and mourned.

-

Life companions — slept beside, washed daily, and featured in myths.

Some cattle boast horns taller than an average human, bred over generations for symmetry and grandeur. These aren’t just aesthetic — they’re symbolic of beauty and prestige. Just as some cultures revere sports cars or designer fashion, here, horns are the crown.

In Mundari cattle camps, the line between man and beast blurs. People cover themselves in ash — a natural insect repellent and sacred cosmetic — and sit peacefully among their herds. In this dusty ballet, a silent code exists, where trust, care, and harmony shape every interaction.

Ash, Urine, and Identity: Sacred Aesthetics

To outsiders, the sight is surreal: men with bleached orange hair, bodies glistening in ash, scarification patterns carved into the skin.

But here, these are more than traditions. They are expressions of pride, purity, and spirituality.

-

Urine from cattle is used to dye the hair of young men — turning it into a brilliant saffron hue, signaling youth, beauty, and virility.

-

Ash from burnt cow dung is used daily — it protects from insects, enhances body contours, and creates a ghostly aesthetic in the dawn mist.

-

Scarification, often done without anesthesia, tells stories of bravery, kinship, maturity, and sometimes grief.

These practices may seem extreme, but to the Dinka and Mundari, they are no stranger than makeup or tattoos are to the Western world. Each mark, color, or ritual holds history — often passed down for centuries.

When Medicine Met Mystery: Ancient Trepanation

Now, let’s go deeper — into the skull.

Trepanation — the act of drilling or cutting into the human skull — is one of the oldest surgical practices in the world. It sounds brutal, and it was. But it was also remarkably successful in some cultures.

The Inca civilization had survival rates as high as 85%. In comparison, European medieval trepanation was often deadly. Skulls found in Peru show individuals who underwent the procedure up to seven times — suggesting not only survival but repeat attempts as treatment.

While there’s no archaeological evidence of trepanation in South Sudan yet, the intertwining of spirituality and healing is deeply embedded in Dinka and Mundari culture.

When someone suffers seizures, mental illness, or trauma, traditional beliefs often attribute this to spiritual disturbance — sometimes requiring community rituals, herbal medicine, or spiritual exorcism. Modern science might scoff — but modern neurosurgery also removes parts of the skull to relieve pressure. Is it so different?

Bones That Speak: The Science of Ancient Survival

How do we know if a trepanation patient lived?

Archaeologists look for bone remodeling — evidence that the skull began to heal. If the edges are smooth and the bone is regrowing, it means the patient survived for weeks or months, maybe even years.

In some ways, the bones of the dead speak louder than words ever could — telling us about ancient bravery, experimental medicine, and the value of life in a world without hospitals.

Sculpted by Survival: Body as Biography

The Dinka and Mundari aren’t just tall — they are physiological marvels, shaped by generations of environmental pressure and adaptation.

-

Minimal body hair helps regulate heat in extreme equatorial climates.

-

Long limbs and lean frames maximize surface area, aiding cooling.

-

Strong calves and endurance reflect a life of walking, herding, and dancing under the open sun.

These physical traits are not cosmetic — they are functional. They represent the ultimate survival toolkit for life in a harsh but beautiful land.

But there’s a tragic note too. Years of war, famine, and displacement in South Sudan have stunted growth in newer generations. Malnutrition has lowered average heights. This shows how deeply environment and trauma affect even genetic expression.

Faith, Spirits, and Mental Health: Demons or Diagnoses?

Imagine someone in your village collapses, shakes, or begins talking incoherently. Without access to neurology or mental health care, what would you believe?

In many cultures — from medieval Europe to modern tribal societies — the answer was spiritual possession.

This wasn’t superstition born from ignorance. It was a survival mechanism, a way of creating shared narratives and healing rituals in the absence of science. And often, it worked — not because of exorcisms per se, but because communal care helped the afflicted feel supported and less alone.

Even today, traditional healers remain vital in rural areas, offering emotional support, herbal remedies, and symbolic healing — all of which can have real psychosomatic effects.

The Danger of Misuse: Race, Evolution, and Pseudoscience

When talking about height, genetics, or adaptation, it’s essential to avoid slipping into race-based pseudoscience.

Yes, different populations evolve differently — because of environment, lifestyle, and culture. The Dinka may be tall; the Sherpas may be high-altitude champions; the Bajau of Southeast Asia may hold their breath for five minutes underwater.

None of these traits imply superiority or inferiority — only difference. Understanding human variation should inspire awe, not division.

As evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould once said:

“Humans are not better than other species; we are simply a different way of being alive.”

South Sudan Today: Between Recovery and Resilience

South Sudan has endured decades of war, famine, and political instability. Since its independence in 2011, progress has been slow, and conflict still lingers in many regions.

Yet amid the hardship, the spirit of its people endures. Culture is not just surviving — it’s resisting extinction.

New generations are using photography, documentaries, and art to tell their stories. The Dinka and Mundari are now appearing in global exhibitions, fashion features, and academic studies — not as relics of the past, but as voices of the present.

Can You Visit South Sudan? Yes — With Caution and Care

South Sudan is not for the casual tourist. But if you are committed, informed, and deeply respectful, travel here can be life-changing.

✈️ Travel Tips:

-

Visa: Most nationalities need to apply for a visa in advance.

-

Guides: You’ll need a trusted fixer, often through NGOs, journalists, or anthropologists.

-

Seasons: Travel during the dry season (December–March) to avoid flooding.

-

Photography: Always ask permission. Some believe the camera captures more than just images.

-

Safety: Stay updated on political developments. Avoid conflict zones.

-

Support: Buy local — crafts, carvings, photography, food. Every coin matters.

Why It Matters: The Human Story Lives Here

In the cattle camps of South Sudan, you won’t find resorts or influencers. But you will find humanity at its most unfiltered — ancient, resilient, and stunningly poetic.

You’ll see how communities survive, celebrate, and evolve — without losing their connection to land, ancestry, or belief.

This is not a place that asks to be judged. It asks to be witnessed.

In the Echo of Horns and Ash

South Sudan isn’t a tourist destination — it’s a calling. It’s a place for those who want more than just snapshots. It’s for those who want stories etched into their soul.

In the firelight, you’ll see ash-covered warriors. In the morning mist, you’ll hear cattle songs. In the eyes of elders, you’ll glimpse the memory of centuries.

And when you leave — if you ever truly do — you’ll carry something different.

Not just souvenirs.

Not just photos.

But a deeper understanding of what it means to be human.